Let’s Change Parent/Teacher Conversations About Reading

By Mark W.F. Condon, Unite for Literacy vice president

It is time to change the “common” conversations families and schools have around early literacy. It is not enough for teachers and parents to care whether children learn to read books well because the value of reading a book with kids does not have to do with only reading the words. Children themselves must enjoy and care about reading and books.

One of the best supports for children is when parents and teachers collaborate—talking together about how to inspire our youngest children (even babies!) to fall in love with the richness of book reading. Schools alone cannot do it. Parent/teacher conversations about books and about reading them with a child from birth onward is critical.

It seems that far too many families need to understand what the simple act of expressively reading aloud to their babies can do for them as they grow. They need to be given compelling evidence of the impact that animatedly reading and talking about books will have on language growth and on children’s attention to books. This is particularly crucial during their earliest years from birth to age 5, the period during which 90 percent of children’s brains’ physical structure is developing. Children’s daily engagements with books contribute to their language ability and eagerness to use books to explore the world beyond home. The impact is massive and the speed of this advancement is almost inconceivable!

Take Ada, a two-year-old who is completely mesmerized by books and has been since she was an infant. Though their family is always on the go, "Reading is Ada’s favorite thing to do,” her mom Kimmy told me when Ada was just a couple of months old. How is that possible? Well, her parents read and talk with her daily and have always talked with her about everything they do during the day, as they also do with Ada’s 9-month-old twin brothers, Finn and Hugo.

While Kimmy holds the twins on her lap, a picture book opened between them, Ada pours over other books on her own, sitting with them strewn around her. She revisits her favorites over and over, studying the illustrations. And though her conversational language is still limited, she is always talking as she interacts with books and her other toys. It is a delightful ongoing narrative that includes expression and a cadence that reveals she has been listening closely. Ada constantly amazes her parents with her latest vocabulary, most of which she has internalized from them reading to and talking with her about books and commenting on them along with her other kinds of play.

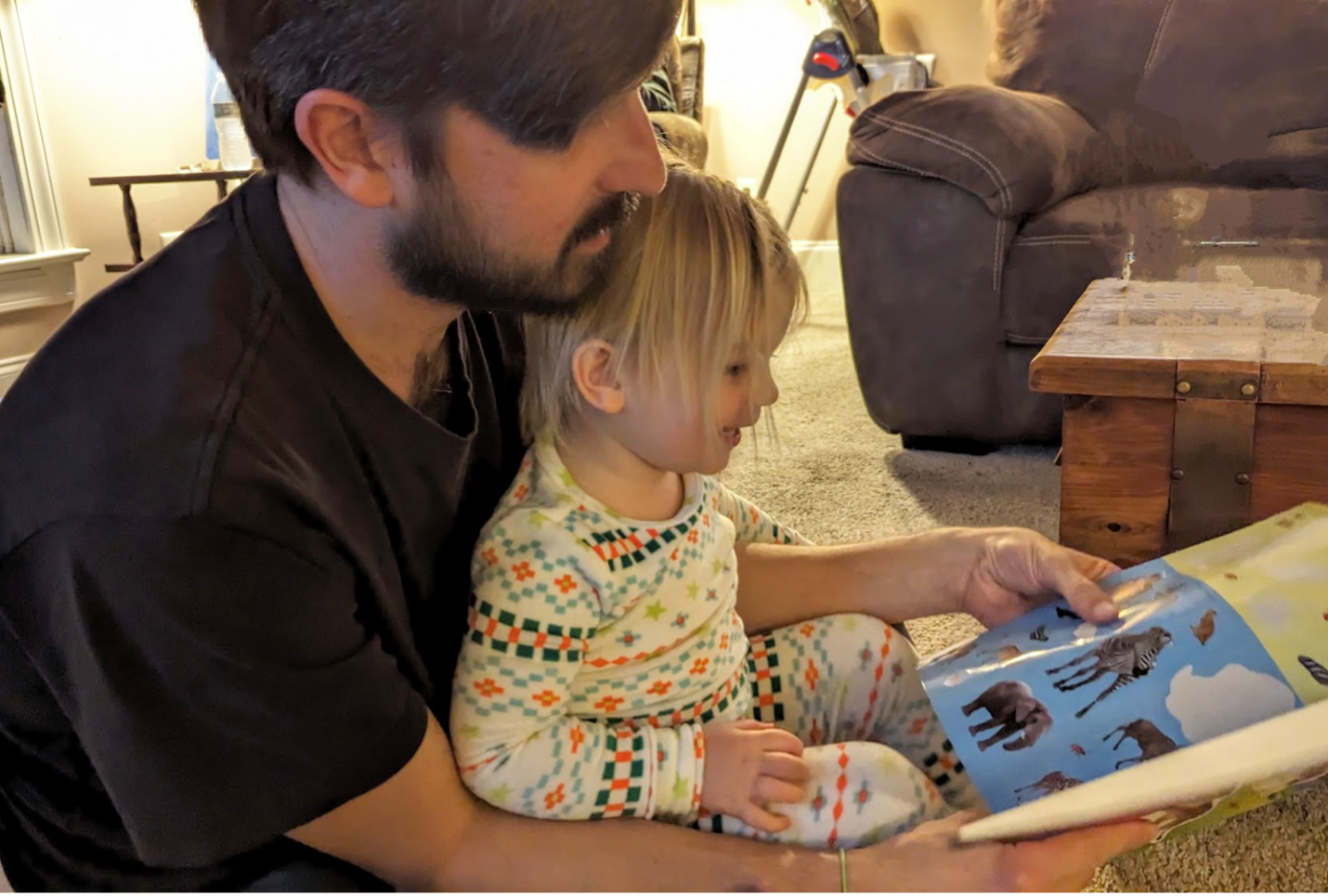

What is typically happening in school, while important, pales in comparison to the power of what happens in this family that is so naturally developing a culture of reading as Ada, her twin brothers and her parents enjoy books together. Let us eavesdrop on Ada and her daddy, Luke, as they “read” through an animal sticker book.

Father and daughter are reading a book featuring white silhouettes in the shapes of animals in various habitats. Corresponding stickers with each animal are collected on pages in the back of the book. Ada flips back and forth, searching for white shapes of interest on each page, then flips again to the back to study animal choices. She is already located a “mon-ka-me" (monkey), a fish, a lion, and an elephant.

When they get to the Wild Africa page, Ada spies another shape she recognizes—a giraffe—and returns to the sticker page to look for it. She points to the animal, daddy peels the sticker from the page and hands it to Ada, who flips back to the West Africa page to locate the animal’s silhouette.

“Where does the giraffe go?” asks daddy, as they survey the page pair together.

“In the water,” Ada says, holding the shape toward the bottom of the page, above the lagoon pictured in the book.

“Oh, yeah. Could be,” daddy agrees. “Could be bathing,” he offers, validating Ada’s suggestion. “Where are the other giraffes?” Ada moves her sticker closer to tall creatures near some trees. “So, you think he’d like to be hanging around with his family—with his mommy?”

“I want mommy,” she says, pressing the sticker on a white space on the page with daddy’s help. Ada then flips to the sticker page again, announcing her intent. “I want daddy.”

As Ada and her daddy study this book together, examining species and problem-solving where each animal belongs, the conversation is supportive of Ada’s thought processes and her father’s comments encourage her explorations. He runs alongside her, offering observations of his own, confirming her ideas, and occasionally challenging her, like when she held a fish shape over a tree ("No, wait—where do fish live?”). Luke also validates her expected responses, as she determines which animals are of interest, chatting with her about where each animal “lives,” and what distinguishes one animal from another (like the differences between a leopard, tiger and lion).

This family’s engagement with books provides important validation of research that shows that the simple presence of books in a home is associated with elevating the sophistication of a family’s everyday conversation. With the support of her family, avid readers like Ada and her brothers are well on their way to becoming lifelong readers and learners.

If a community’s education system does nothing else, encouraging families to develop cultures of reading should be the primary goal.